Go to a concert these days and look around. The lights flash, the bass shakes your ribs, and the crowd… barely moves. A soft sway here and there. Maybe a few heads bobbing. But mostly, what you see is the cold glow of phone screens, arms extended, faces lit in blue, recording what used to be a shared, sweaty moment of chaos.

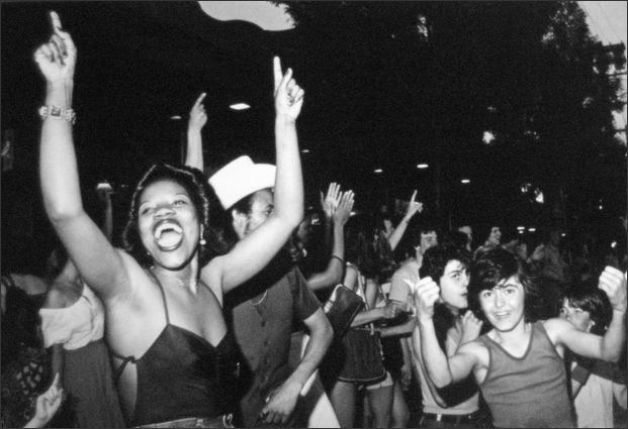

We used to dance. Not well, necessarily, but freely. There was a time when going to a show meant losing your voice and maybe your balance. People jumped, screamed, touched shoulders, and somehow that chaos made sense. Everyone was a little out of sync but together in it, one big, messy rhythm. Now, the average crowd looks more like a polite audience at a museum: still, respectful, recording, preserving. As if movement might break the spell.

Part of this shift comes from how we think about connection. We’ve confused participation with documentation. Sharing a video on Instagram is how we prove we were there.. proof we experienced culture. But the irony is that while we’re capturing the moment, we’re also missing it. The phone becomes a filter, turning an immersive experience into a flat one. We’re there, but not in it.

There’s comfort in stillness, too. Dancing has become an act of exposure. In a sea of cameras, every move feels like it could end up in someone’s story, looped out of context, judged by strangers. The fear of being seen wrong, too loose, too awkward, too much, makes stillness feel safer. Even in a dark crowd, surrounded by music built for release, we hold ourselves back. We curate our presence, even when no one’s asking us to. That fear is part of a bigger cultural shift, one where coolness is controlled. The unbothered posture, the half-nod, the quiet sway, that’s the language of modern concerts. It’s not that we don’t feel anything; it’s that showing it feels risky. Dancing means surrendering the narrative for a few minutes. It’s messy, it’s physical, it’s out of your hands. And in a time where everyone’s image is carefully managed, letting go can feel almost rebellious.

There’s also the way music itself has changed. So many shows now are mediated by visuals: massive LED screens, pre-programmed light shows, perfect sound mixing. Everything is engineered for spectacle. The artist is far away, elevated, untouchable. You’re not in a conversation with the performer anymore; you’re an observer. It’s beautiful, but it’s distant. The intimacy that used to pull people into motion is replaced by awe, and awe tends to keep you still.

Dancing was never about skill, it was about a form of connection. To the music, yes, but also to each other. When people moved together, even if they didn’t know each other’s names, there was a shared current. You didn’t have to talk. You didn’t even have to be good. You just had to be. The beat handled the rest. Now, concerts can feel like parallel experiences– thousands of people in the same space, having entirely separate nights. Some are filming for content. Some are watching the stage through their screen. Some are just… standing. It’s strange, this collective solitude. We’re together, but not together.

Maybe it’s unfair to expect music to mean what it once did. The world is different. Technology changed how we remember and how we share. But maybe we lost something small and essential along the way, the willingness to look foolish for the sake of joy. To let the rhythm have us instead of the other way around.

Still, the story isn’t all bleak. Every once in a while, you stumble into a crowd that remembers how to surrender. With their reunion.. Oasis is an example of this. Their fans still treat “Don’t Look Back in Anger” like a communal exorcism. The second that piano intro drops, something cracks open, shoulders loosen, voices lift, and suddenly the whole room is swaying with the emotional confidence of people who don’t care how they look. It’s not dancing in the technical sense, but it’s movement with a pulse, the kind that comes from the gut rather than the camera roll.

Oasis isn’t alone. Acts that build their audience based on community and experience somehow pull genuine motion out of crowds that were otherwise glued to their screens, no matter the genre. A Fred again.. set feels almost anthropological: people rediscover how to bounce, hug strangers, let the beat shake the stiffness out of their bodies. Idles shows turn into joyful riots, where awkwardness dissolves in the noise. Some clubs and small festivals still manage it too. Local punk scenes, where half the audience knows each other by name, still blur into living, breathing motion. Iit still happens in smaller rooms. You’ll find it at DIY gigs, local scenes, warehouse parties, the rare spaces where people feel invisible enough to move. Where the music is loud enough to drown out self-consciousness. Where no one’s filming because everyone’s too busy living. In those moments, the energy is raw, almost prehistoric, a reminder that movement is the body’s way of saying “I’m here.”

These moments matter because they show the muscle isn’t dead, it’s just out of shape. Give people the right conditions: a sense of safety, a pocket of anonymity, a song that cuts through the noise, and they remember. The body remembers. The room remembers. For a second, the modern instinct to self-curate gets drowned out by something older and less managed.

So maybe the real takeaway isn’t that we’ve stopped dancing. It’s that we’re out of practice. The impulse is still there, waiting for one song, one drop, one line everyone knows by heart. And when it happens, the whole space changes. Suddenly it’s warm again. Suddenly people aren’t just attendees– they’re participants.

The world is noisy and self-conscious to the point of paralysis. But the right band, at the right moment, can still break through all that and make a room move like it remembers what joy feels like. The spark never disappeared. It just needs more coaxing now.

And once it lights up, even briefly, it reminds you that dancing isn’t a lost ritual. It’s a dormant one. That’s a much better place to start from.